|

|

TRANSLATIONS IN KHMER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Documentation Center of Cambodia translates books from English

into Khmer (Edited by Youk Chhang); we do not translate from Khmer into other languages.

Please also note that DC-Cam does not fund the translation or

publication of books. The authors are responsible for this, or for

locating funding for both purposes

|

|

|

|

|

|

First They Killed My Father:

A Daughter of

Cambodia Remembers

Loung Ung

Translated by Norng Lina

2002

(USD15)

In this book, Loung Ung tells the story of her life under the Khmer Rouge.

When she was five years old, she and her family were forced to leave their

comfortable life in Phnom Penh when the Khmer |

|

Rouge took control of the country. Ms. Ung was trained as a

child soldier, while her other siblings were sent to labor camps.

After the regime fell, she and her surviving siblings slowly

reunited.

Funding provided by the author.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

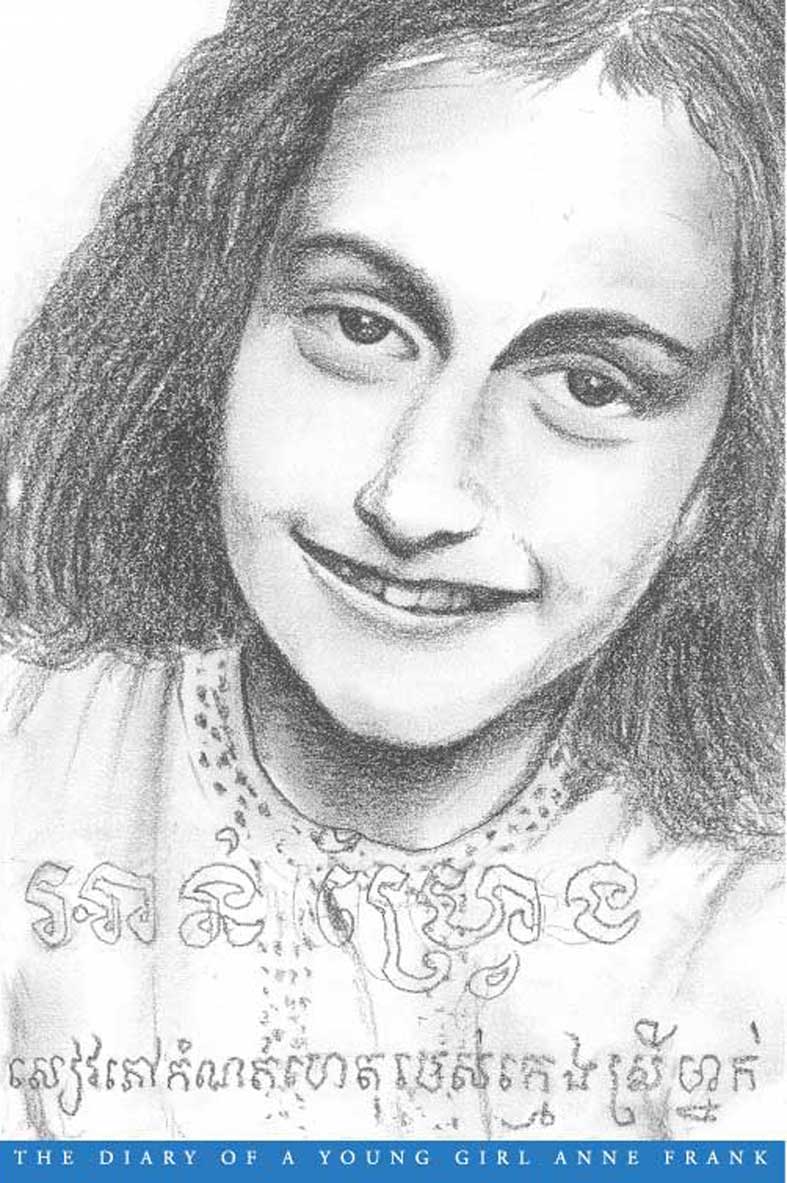

The Diary of a Young Girl

Anne Frank

Translated by Ser Sayana

2002

First published in 1947, millions of people have read the diary of

13-year old Anne Frank. She and other members of her family hid

in the back of an

Amsterdam warehouse for two

years in an attempt to escape detection by the Nazis. Anne Frank

died in the |

|

Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in March 1945, three month before

her 16th birthday.

Funding provided by the Government of the Netherlands, Bangkok, Thailand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

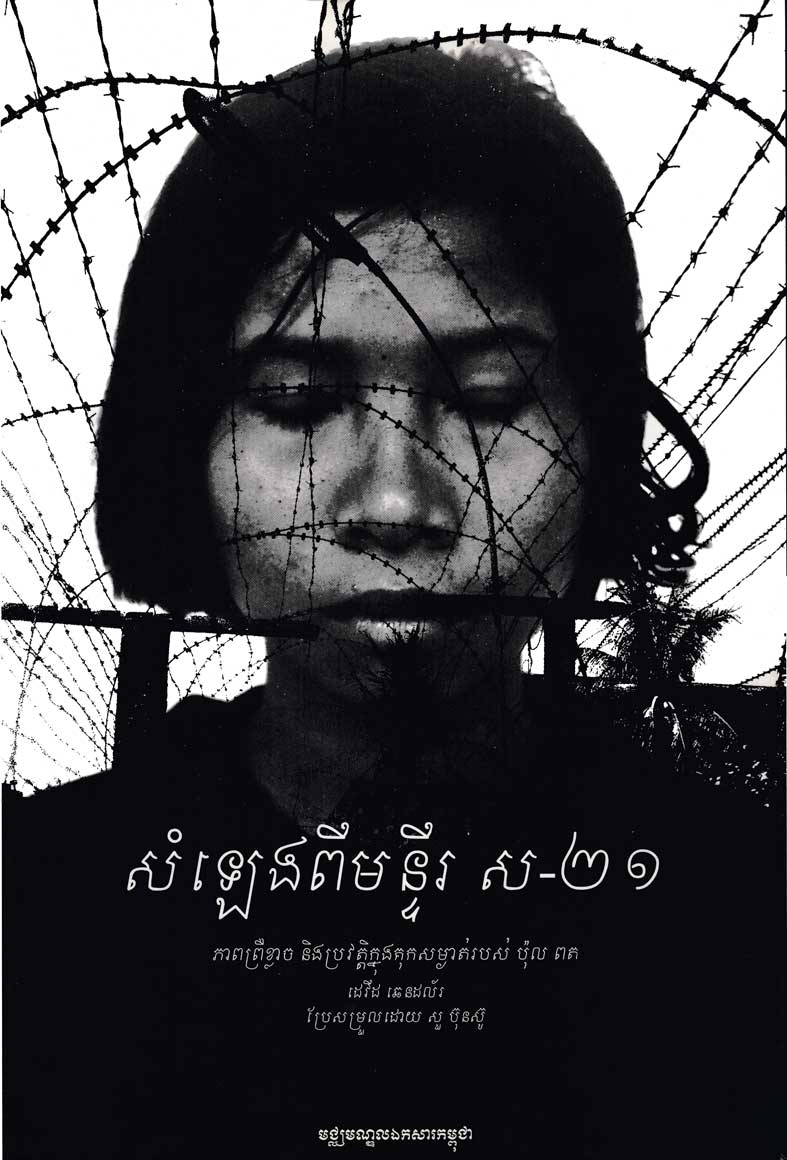

Voices from S-21:

Terror and History in Pol Pot’s Secret Prison

David Chandler

Translated by Sour Bonsou

2003

(USD10)

Historian

Chandler

examines the Khmer Rouge regime through S-21, a secret prison in

Phnom Penh where over 14,000 people died and less than a dozen

survived. Using archival materials and |

|

interviews with survivors, he traces the culture of obedience and

its attendant dehumanization, which made it easier for the Khmer

Rouge to torture and kill their “enemies.”

Funding provided by US Agency for International Development, the

Government of the Netherlands, and the Government of Sweden.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

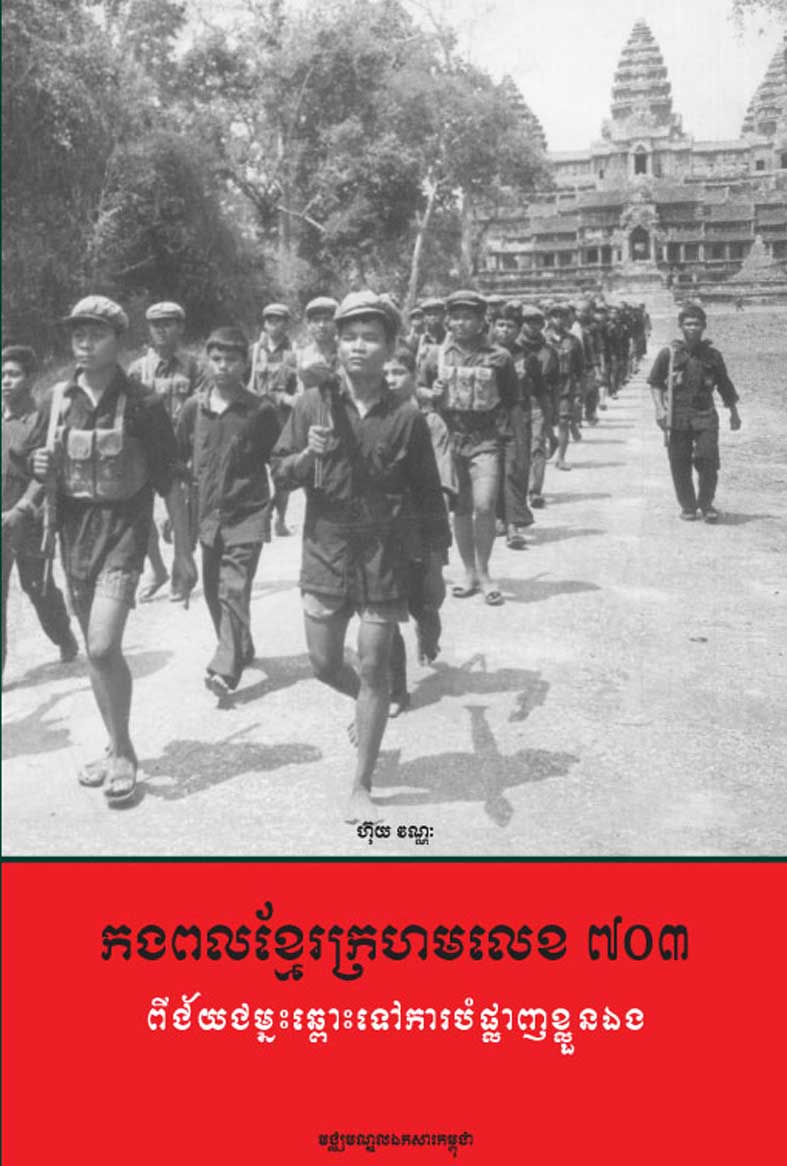

The Khmer Rouge Division 703:

From Victory to Self-Destruction

Vannak Huy

2003

(USD15)

One of the most favored of the Khmer Rouge’s nine military

divisions, Division 703 was composed of 5,000 to 6,000 peasants,

primarily from Kandal province. At the end of 1975, its soldiers

with |

|

“clean” backgrounds were given positions at Tuol Sleng (the

central-level prison also known as S-21) or its branch office S-21D

(Prey Sar prison) and various government offices. At least 567 of

these men were later branded as “enemies” of the regime and executed

at S-21.

This monograph examines the careers of 40 soldiers who worked in

Division 703. Most of those who survived the 1979 defeat of the

Khmer Rouge returned to their villages in the early 1980s, often

after spending time in prison as a result of their involvement with

the regime.

Funding

provided by the United States Department of State, Bureau of

Democracy, Human Rights and Labor.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lucky Child

Loung Ung

Translated by Phat Rachana

2004

Cambodian-American Ung’s memoir describes her life in America and

contrasts it with that of her sister, who remained in Cambodia after

the Khmer Rouge regime fell. |

|

Funding provided by the author.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

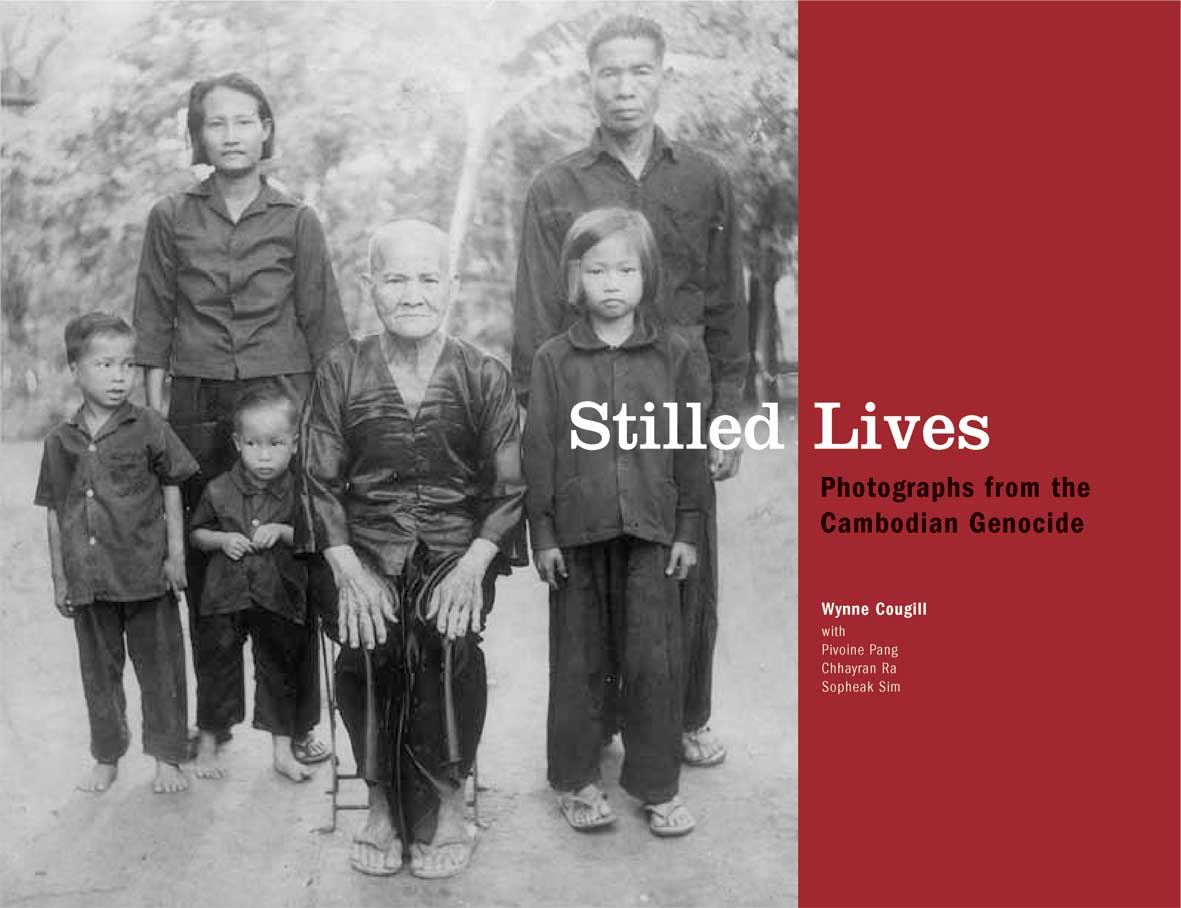

Stilled Lives:

Photographs of the Cambodian Genocide

Wynne Cougill with Pivoine Pang, Chhayran Ra, and

Sopheak Sim

Translated by Chy Terith

2004

(USD15)

|

This book contains photographs and essays on the lives of 51 men and women, who joined the Khmer Rouge during the 1960s and 1970s. They were what the Khmer Rouge called “base people”: those from the peasant class who generally were treated less harshly than the “new people” (city dwellers and those associated with the former Lon Nol regime). The people profiled here served the Khmer Rouge as farmers, soldiers, security personnel, or cadres (those with some degree of command responsibility). Although most Cambodians view the former Khmer Rouge as cruel and sometimes evil, this book shows that they and their families faced the same struggles and hardships as their victims, and points to our common humanity.

Funding provided by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Histoire du Cambodge

Depuis Le 1er Siècle

de Notre

Ère

Adhemard Leclère

Translated by Tep Meng Kheang

2005

(USD20)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the War Was Over:

Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution

Elizabeth Becker

Translated by Sokha Irene

2005

(USD20)

Reporter Becker, who covered Cambodia for the Washington Post,

examines the historical patterns of violence and authority in

Cambodia that allowed the Khmer Rouge to ascend to power and |

|

made the genocide possible. She also examines the roles of the

United States

and other members of the United Nations in betraying Cambodia. The

book is based on the author’s personal experiences and interviews

with Cambodian leaders and ordinary citizens.

Funding provided by US Agency for International Development (USAID),

the Government of Sweden and the US Embassy in Phnom Penh.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

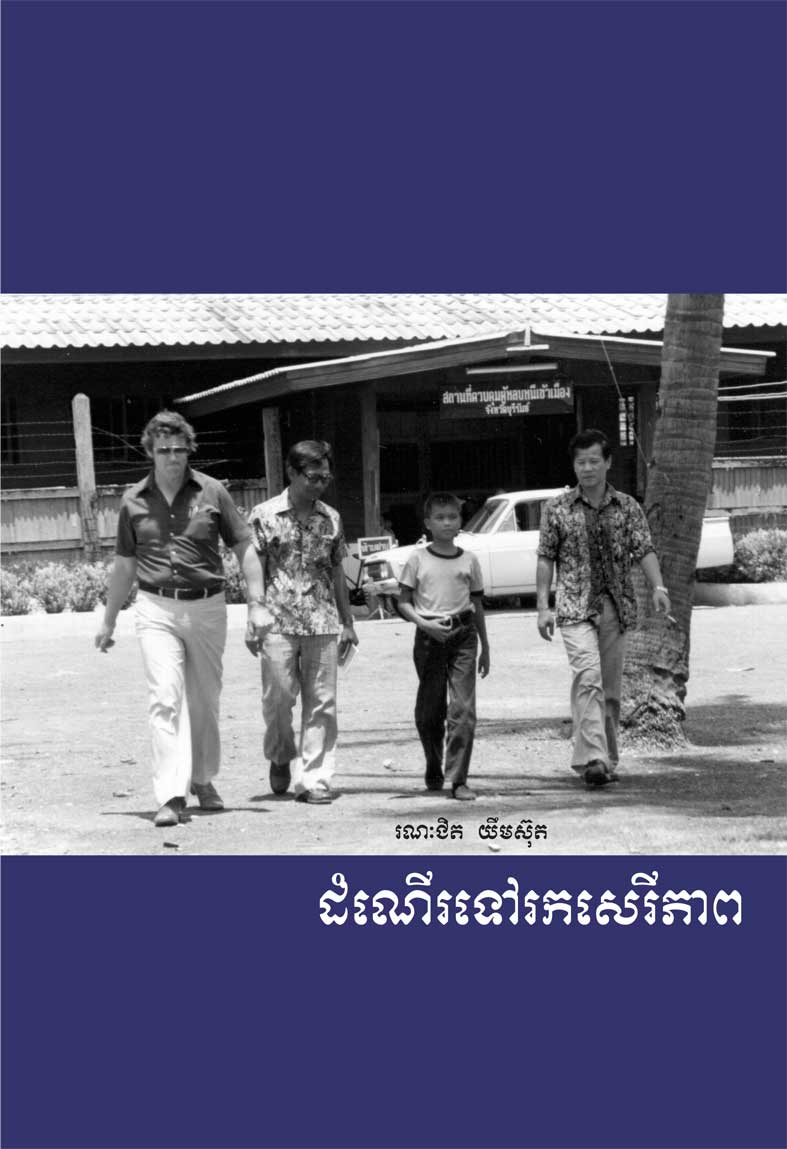

Journey to

Freedom

Ronnie Yimsut

Translated by Eng Kok-Thay

2006

(USD15)

In this memoir, Cambodian-American Yimsut recalls his experiences

as a 15-year old boy who survived five years of civil war, three

years in a labor camp, Thai prison, and refugee camps before

becoming a |

|

naturalized

US citizen.

Funding provided by NZAID (New Zealand) and the author.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brother Enemy

Nayan Chanda

Translated by Tep Meng Khean

2007

(USD20)

This book by the bureau chief for the Far Eastern Economic

Review examines the third Indochina War and offers an

explanation for the Cambodian genocide. Chanda posits that the Khmer

Rouge built their revolution at breakneck speed to prepare for a

life-and- |

|

death struggle against the Vietnamese, and the means they used to

do this was ideological “purification.”

Funding provided by the Government of Sweden and US Agency for

International Development.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

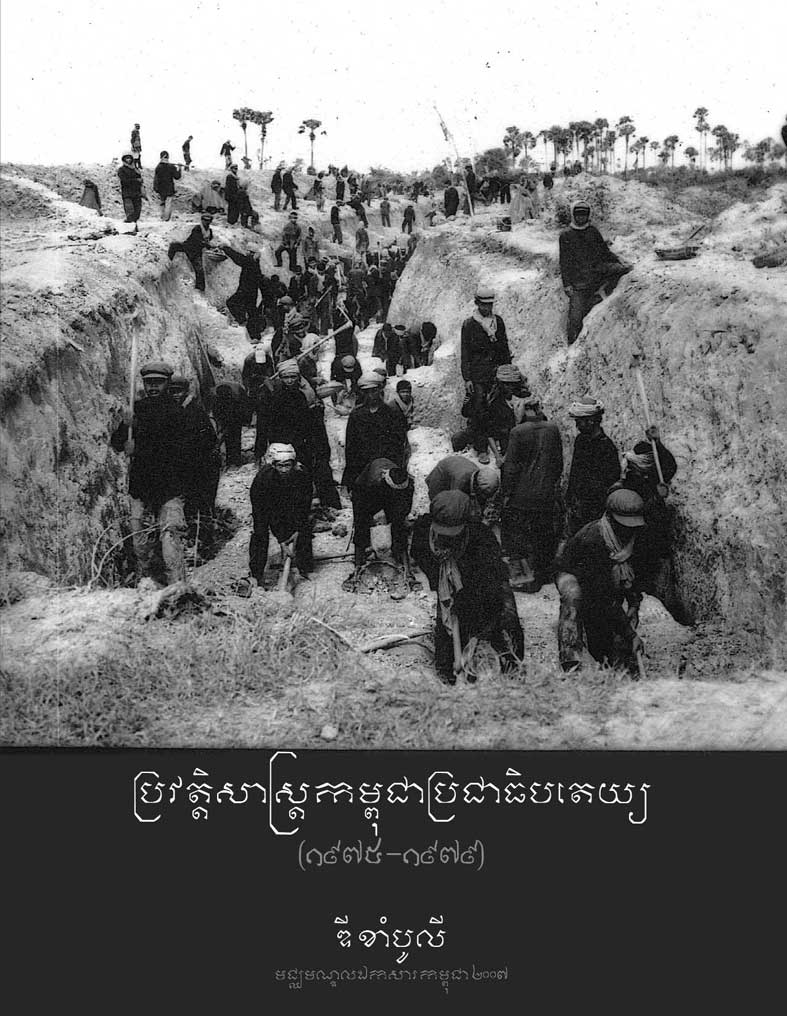

A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)

Khamboly Dy

2007

(USD7)

Chinese diplomat Chou Ta-kuan gave the world his account of life at Angkor Wat eight hundred years ago. Since that time, others have been writing our history for us. Countless scholars have examined our most prized cultural treasure and more recently, the Cambodian |

|

genocide of 1975-1979.

But with

Khamboly Dy’s A History of Democratic Kampuchea, Cambodians

are at last beginning to investigate and record their country’s

past. This new volume represents two years of research and marks the

first such text written by a Cambodian.

Writing about

this bleak period of history for a new generation may run the risk

of re-opening old wounds for the survivors of Democratic Kampuchea.

Many Cambodians have tried to put their memories of the regime

behind them and move on. But we cannot progress -- much less

reconcile with ourselves and others -- until we have confronted the

past and understand both what happened and why it happened. Only

with this understanding can we truly begin to heal.

Intended

for high school students, this book is equally relevant for adults.

All of us can draw lessons from our history. By facing this dark

period of our past, we can learn from it and move toward becoming a

nation of people who are invested in preventing future occurrences

of genocide, both at home and in the myriad countries that are today

facing massive human rights abuses. And by taking responsibility for

teaching our children through texts such as this one, Cambodia can

go forward and mold future generations who work to ensure that the

seeds of genocide never again take root in our country.

Youk Chhang

Director

Documentation Center of Cambodia

The text

was submitted to the Government Working Commission to Review the

Draft of the History of Democratic Kampuchea. On January 3, 2007,

the Commission decided that, "the text can be used as a

supplementary discussion material (for teachers) and as base to

write a history lesson for (high school) students.

Funding for

this project was generously provided by the Soros Foundation’s Open

Society Institute (OSI) and the National Endowment for Democracy

(NED). Support for DC-Cam’s operations is provided by the US Agency

for International Development (USAID) and Swedish International

Development Agency (Sida).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

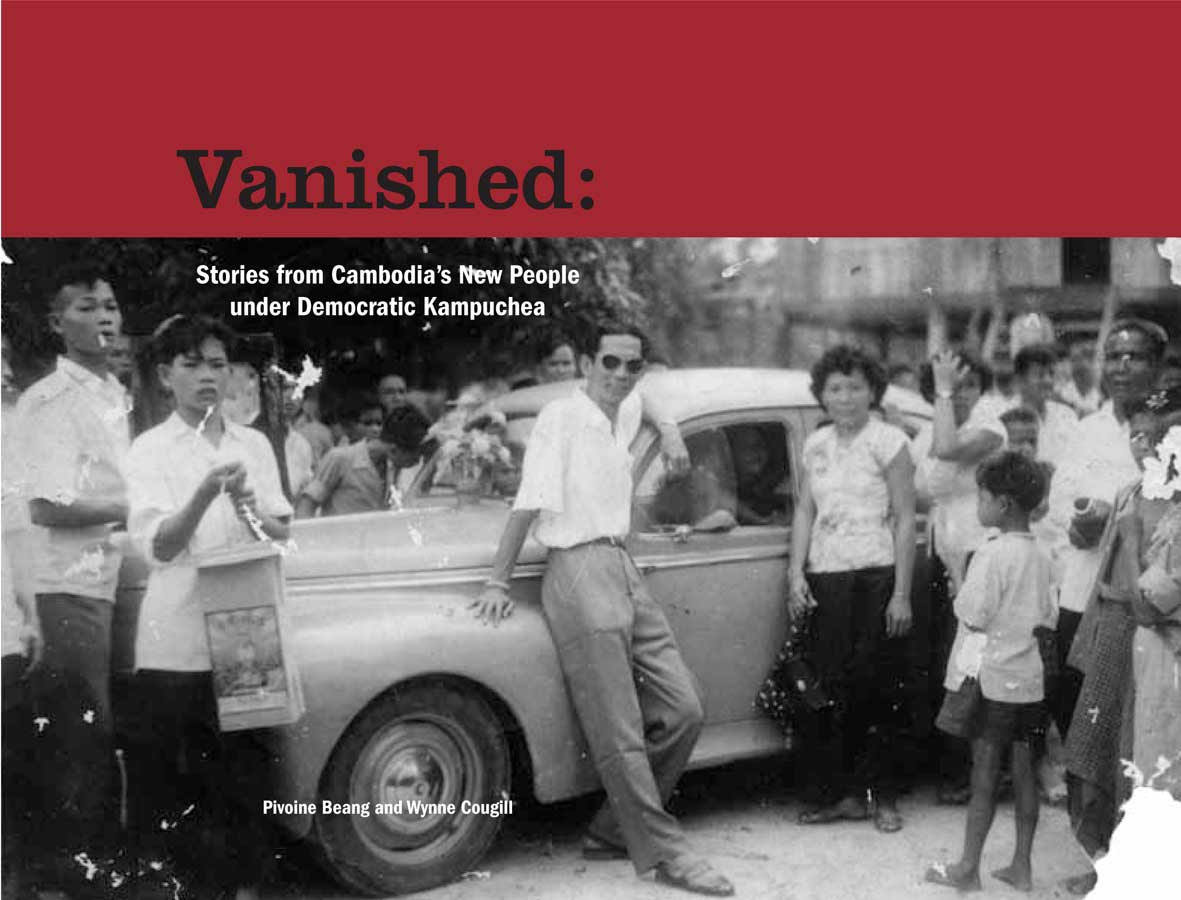

Vanished:

Stories from Cambodia’s New People under

Democratic Kampuchea

Pivoine

Beang and Wynne Cougill

Translated by Chy Terith

2007

(USD15)

|

|

For

centuries, Cambodia’s rural peasants had lived in modest

circumstances with few entitlements, while the country’s tiny urban

elite enjoyed more opportunities and privileges. But in April 1975

when the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia, they reversed this

social order.

Hundreds

of thousands of city dwellers were evacuated to the countryside,

where they were forced into hard labor. Despised by the peasants and

Khmer Rouge cadres alike, these “new people” were viewed as

parasites and imperialists, and their rights and privileges were

removed. As many as two-thirds of them were executed or died as a

result of starvation, untreated diseases, or overwork.

In this

monograph, 52 new people who survived Democratic Kampuchea tell

their stories and those of their loved ones under the Khmer Rouge.

Funding provided by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) with

core support from the Swedish International Development Cooperation

Agency (Sida) and the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Khmer Rouge Tribunal

John D.

Ciorciari

Translated by Dy Khamboly

2008

(USD7)

Between April 1975

and January 1979, the radical Khmer Rouge regime subjected

Cambodians to a wave of atrocities that left over one in four

Cambodians dead. For nearly three decades, call for |

|

justice went

unanswered, and the architects of Khmer Rouge terror enjoyed almost

unfettered impunity. Only recently has a tribunal been established

to put surviving Khmer Rouge officials on trial. This edited volume

examines the origins, evolution, and feature of the Khmer Rouge

Tribunal. It provides a concise overview of legal and political

issues surrounding the tribunal and answers key questions about the

accountability process. It explains why the tribunal took so many

years to create and why it became a "hybrid" court with Cambodians

and international participation. It also assesses the laws and

procedures governing the proceedings and the likely evidence

available against Khmer Rouge defendants. Finally, it discusses how

the tribunal can most effectively advance the aims of justice and

reconciliation in Cambodia and help to dispel the shadows of the

past.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Teacher Guide Book:

The Teaching of "A History of Democratic Kampuchea

(1975-1979)”

Phala Chea, Ed.D, & Christopher Dearing, Esq

Translated by Pheng Pong-Rasy, Dy Khamboly

2010

(USD20)

This

guidebook would not have been possible without the hard work of

countless individuals, some of whom have been instrumental to its

success. I would like to thank H.E. Mr. Im Sethy |

|

for both his

commitment to genocide education for Cambodia’s children and his

commitment to justice for Khmer

Rouge victims. I would also like to thank H.E. Ms. Tun Sam Im for

her tireless efforts to ensure that

genocide education benefits all students in Cambodia. I am grateful

to Dr. Chea Phala and Christopher

Dearing who prepared the text, the translation and editing team, the

24 national and international

teachers, experts, and scholars who helped produce this important

guidebook. Generous financial

contributions from Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Sida (Sweden), USAID

(USA), and Canada, along with

their unyielding support to global genocide prevention and

Cambodia’s future, have also made this

project a reality. Lastly, I wish to thank Dr. Hun Manet whose

support and encouragement helped me get

the textbook, A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979), off the

ground and Mr. Khamboly Dy

for his hard work in writing the first ever textbook on the Khmer

Rouge period.

This guidebook will be used across Cambodian high schools, reaching

an estimated one million students

from grades 9-12. As part of DC-Cam’s Genocide Education Project,

more than 3,000 high school

teachers will be trained on how to teach A History of Democratic

Kampuchea (1975-1979). Only by

leaning from the past can we begin to reconnect all the pieces of

our broken nation. I am humbled to

be one of the servants of this important and noble mission for

Cambodia and for my mother. This project has become the Truth

Commission of Cambodia.

Youk Chhang

Director of Documentation Center of CambodiaFunding provided by the author.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE HIJAB OF CAMBODIA

Memories of Cham Muslim Women after the Khmer Rouge

Farina So

Documentation Series No 16 -- Documentation Center of Cambodia

2011

(USD15)

|

|

This book

examines Cham Muslim women’s experiences under the Khmer Rouge

regime through the complexities of memory and narrative and uncovers

compelling stories of survival and resistance. Khmer Rouge genocidal

policies ruptured ethnic and religious identities and resulted in

the disproportionate death of the Cham group. Guided by their

desire to preserve their families and their cultural identity, Cham

women sometimes complied with Khmer Rouge policies, and sometimes

secretly resisted. Their recollection of this era and lost family

members contributes to the preservation of the Cham identity for

future generations, as well as the collective memories of all

Cambodians.

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR

So Farina

has worked at the Documentation Center of Cambodia since 2003 and is

currently team leader of its Cham Oral History project, which

records the Cham Muslim community’s memories of the Khmer Rouge era

(1975-79). This research monograph, drawn from Ms. So’s master’s

thesis, focuses on Cham Muslim women’s experiences under the Khmer

Rouge.

Ms. So

holds a BA in Accounting and Finance from National University of

Management (Cambodia) and an MA in International Affairs with a

concentration in Southeast Asian Studies from Ohio University (USA).

She has participated in international programs related to genocide,

oral history, Islam in Southeast Asia, memorialization, information

and technology, and truth commissions in Indonesia, Bangladesh,

Thailand, Germany, Malaysia, South Korea, and the United States.

Besides Khmer, her native language, she is fluent in English and

familiar with Bahasa Indo- alay and Cham.

Hijab:

Headscarves are scarves covering most or all of a woman’s hair and

head. The Arabic word hijab, which refers to modest behavior or

dress in general, is often used to describe the headscarf worn by

Muslim women. Muslim women wear the hijab for religious reasons,

including the desire to be judged for their morals, character, and

ideals instead of their appearance.

Funding for

this project was generously provided by the Open Society Foundations

(OSF) with core support from U.S. Agency for International

Development (USAID) and Swedish International Development Agency (Sida).

|

|

|

|

|

|

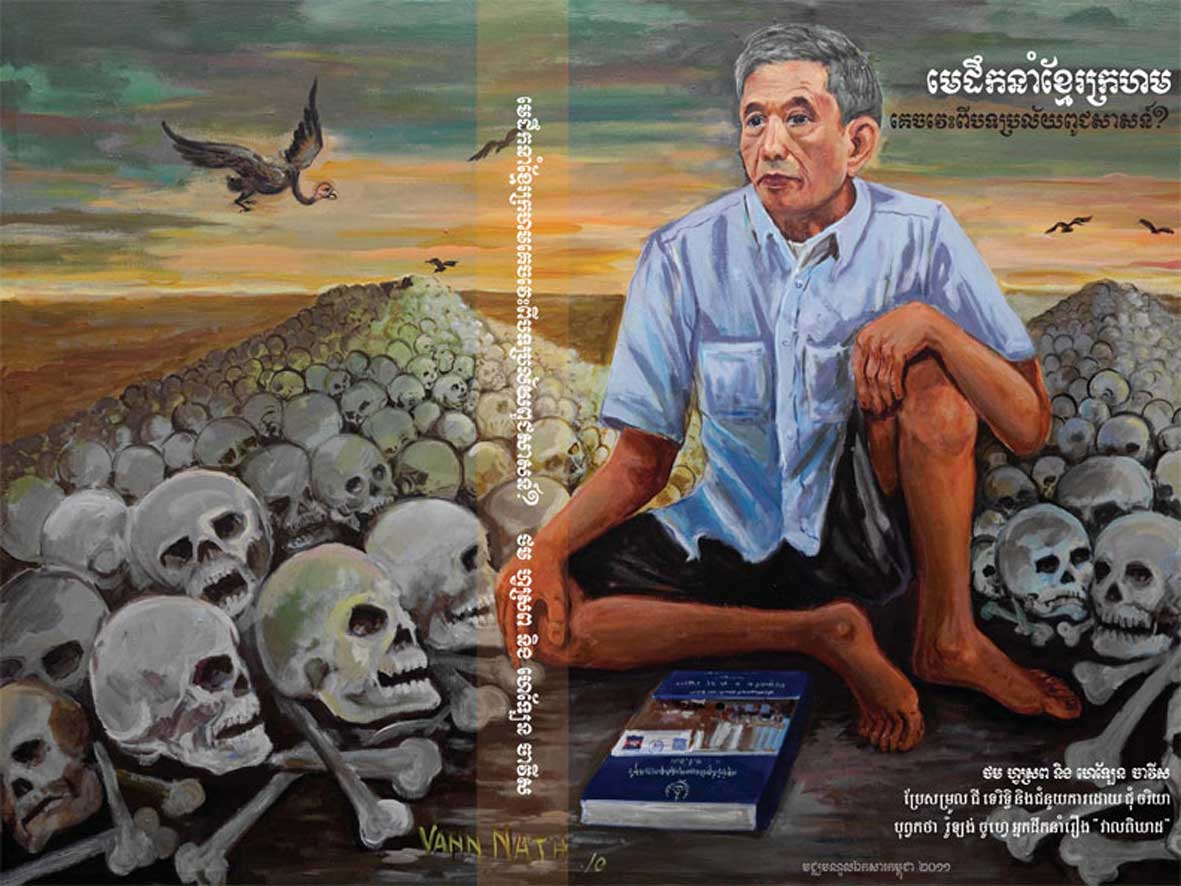

This Khmer Translation is dedicated to Vann Nath, famous Cambodian

painter and one of the few survivors of Tuol Sleng prison, who died

on 5 September 2011, just as this book was in the final stages of

production. The cover is Vann Nath’s untitled last major work

depicting Duch as he faces the consequences of his crimes, sitting

in a field of skulls of the victims with the judgment of the Trial

Camber of the ECCC in front of him. (Vann Nath’s family kindly gave

permission to us to reproduce this work. Photo courtesy of Jim

Mizerski)” |

Getting Away with Genocide?

Elusive Justice and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Helen Jarvis and Tom Fawthrop

Translated by Chy Terith with Chum Charya

2011

(USD12)

Twenty-five years

after the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime, not one Khmer Rouge

leader has stood in court to answer for their terrible crimes. Tom

Fawthrop and Helen Jarvis show how governments that often speak the

language of human rights shielded Pol Pot and his lieutenants from

prosecution during the 1980s. After

Vietnam ousted the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979, the US and UK

governments backed the Khmer Rouge at the UN, and approved the

re-supply of Pol Pot’s army in

Thailand. The authors explain how, in the late 1990s, the forgotten

genocide became the subject of serious UN inquiry for the first

time. Finally, in 2003, the UN and the

Cambodian government agreed to hold a trial in Phnom Penh conducted

jointly by international jurists and Cambodian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

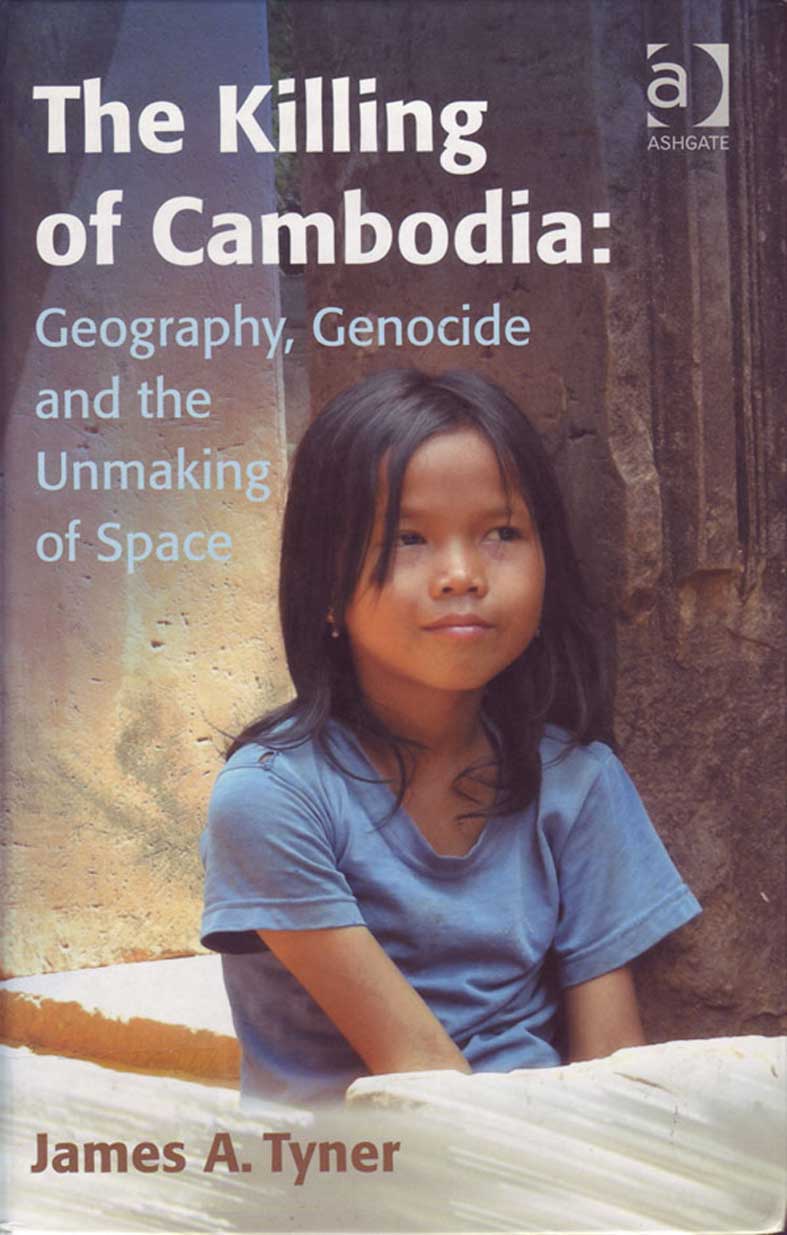

The Killing of Cambodia:

Geography, Genocide and the Unmaking of Space

James A. Tyner

Translated by Y Manoka, Keo Ratanatepy,

Kouy Bun Rong, Veng Visal

2012

Bio of Translators

Between 1975 and

1978, the Khmer Rouge carried out genocide in |

|

Cambodia

unparalleled in modern history. Approximately 2 million died –

almost one quarter of the population. Taking an explicitly

geographical approach, this book argues whether the Khmer Rouge's

activities not only led to genocide, but also terracide – the

erasure of space.

In the Cambodia of 1975, the landscape would reveal vestiges of an

indigenous pre-colonial Khmer society, a French colonialism and

American intervention. The Khmer Rouge, however, were not content

with retaining the past inscriptions of previous modes of production

and spatial practices. Instead, they attempted to erase time and

space to create their own utopian vision of a communal society. The

Khmer Rouge's erasing and reshaping of space was thus part of a

consistent sacrifice of Cambodia and its people – a brutal

justification for the killing of a country and the birth of a new

place, Democratic Kampuchea.

While focusing on Cambodia, the book provides a clearer geographic

understanding to genocide in general and insights into the

importance of spatial factors in geopolitical conflict.

|

|

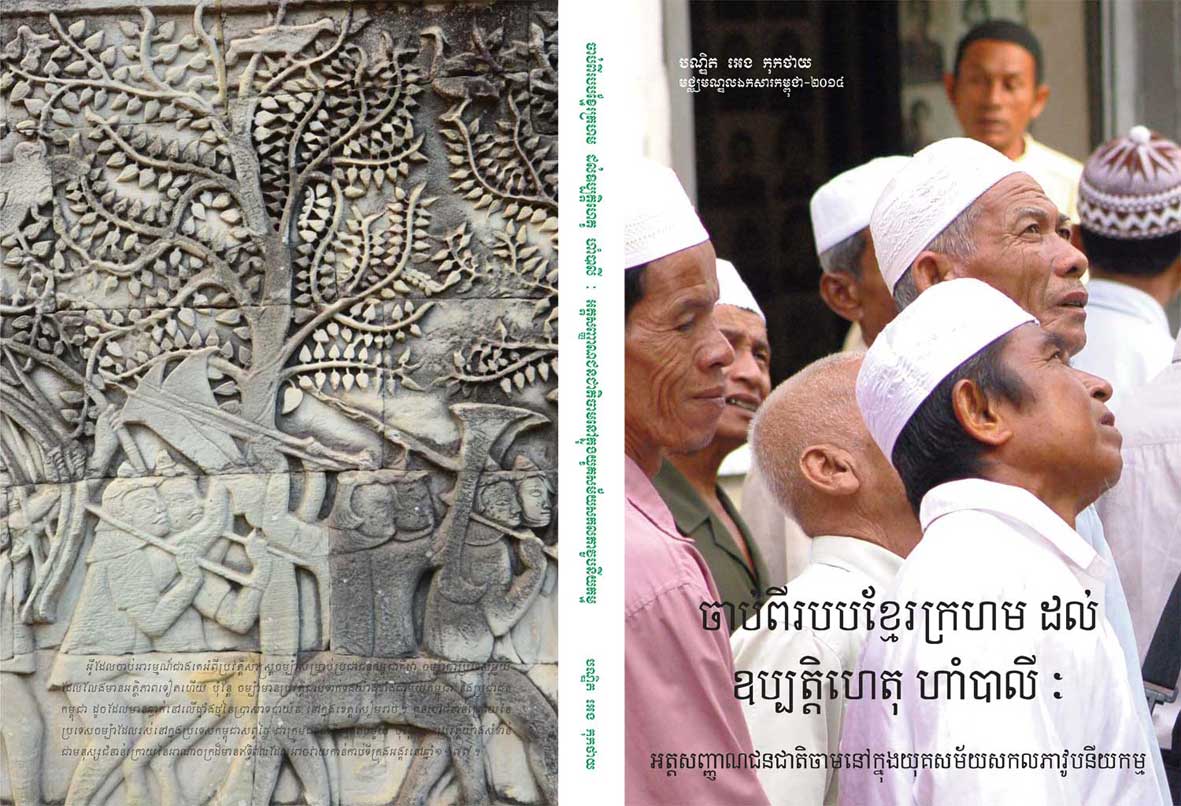

From The Khmer Rouge to Hambali:

Cham Identities in a Global Age

Kok-Thay ENG, Ph.D.

Translated by Huy Samphors, Sirik Savina

2014

(USD12) |

|

This book explores different forms of Cham identity in relation to this minority's history,

society and culture. It has three goals: first, to provide the most comprehensive overview

of Cham history and social structure; second, to illustrate how Cham identities have

changed through time; and third, to consider whether in the aftermath of Democratic

Kampuchea and the Cold War Cham became radicalized. Its theoretical position is that the

group's religious, ethnic and other social identities can be classified as core (those that are

enduring) and peripheral (those that are more changeable depending on new social and

global contexts). Core identities include being Muslim (religious) and descendants from

Champa whose indigenous language is Cham. Peripheral identities are sectarian, economic

and political.

As immigrants to Cambodia, Muslims, and victims of genocide, the Cham have been

associated with terrorism. In the process of constructing their peripheral identities, after

genocide and especially after the Cold War, they are suspected by some Khmer, foreign

governments and international observers of having links with, attempting to and

committing acts of terrorism, both in Cambodia and southern Thailand. Other factors such

as weak secular education, unregulated and open Islamic revival, and the strong need for

overall community development, such as improved living standards and education, led to

further suspicions of terrorism. Cambodia's weak rule of law, fledgling financial system,

immature anti-terrorist measures, corruption and porous borders also contributed to the

terrorist stigmatization of the Cham.

Terrorism is at the pinnacle of the problems facing the Cham in their attempt to revive

their community and reconstruct their peripheral identities. Little has been studied about

the Cham. By examining the Cham's origins in Champa, their arrival in Cambodia, religious

conversion, political affiliations, and social structure, it is possible to understand better

their core identities as ethnic Cham and Muslims and whether they have become

radicalized. In addition, this book will shed light on the ways in which their peripheral identities change over time and how these identities are affected in an age in which Islamic

revival, global aid and terrorism bring fresh challenges to the community.

This research seeks to contribute to the study of identities of an Islamic and ethnic

minority group in a Buddhist majority country as the group recovers from genocide, is

increasingly exposed to global flows, and suffers from the threat of being pulled into global

terrorism. It seeks to contribute to our understanding of the Cham which receives little

scholarly attention. It also attempts to contribute to the study of identity.

Author Biography:

Eng Kok-Thay: Kok-Thay received his Ph.D. Degree in Global Affairs at Rutgers University in

2012. Born into an impoverished family in Chi Kreng district, Siem Reap province, Kok-Thay

is the only son in a family of five siblings. As a child Kok-Thay frequently swam Chri Kreng

River, which he jumped into from an ancient bridge spanning the river. Chi Kreng district is

an area around Tonle Sap Lake where the Khmer Rouge frequently attacked in the 1980s

and early 1990s. Accordingly, Kok-Thay's family fled to Siem Reap provincial town in 1991.

Angkor temples became his playground, although some of the temples were still controlled

by the Khmer Rouge. Attempting to understand the Cambodian genocide and civil war,

Kok-Thay volunteered for the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) in 2001. Kok-

Thay translated "The Journey into Light," a historical autobiography by a Cambodian

American, which was published in 2005. Before coming to Rutgers University, Kok-Thay

received his M.A. in Peace and Conflict Studies from Coventry University. In 2007, Kok-Thay

completed his M.S. degree in Global Affairs with support of a Fulbright Scholarship.

Currently, Kok-Thay is a Research Director and Deputy Director at DC-Cam. In this capacity,

he has worked with scholars from around the world on their research on Khmer Rougerelated

topics. He is currently supervising several research projects, and he also leads the

Book of Memory project, which aims to document two million names and biographies of

people who died under the Khmer Rouge. His research on the experiences of Cham people

under the Khmer Rouge and their level of radicalism today is also being published by DCCam. |

|

|

|

|

|

A History of The Anlong Veng Community

Khamboly Dy and Christopher Dearing

Translated by Men Pechet

2015

(USD15)

|

|

History invites moral judgments, and in studying the people of Anlong Veng, it is easy to slip into an accusatory mindset. Anlong Veng was the final stronghold of the notorious Khmer Rouge regime—a regime which was responsible for perpetrating genocide, mass atrocity, and incalculable harm on the fabric of Cambodian society. It is believed that over two million people died during the regime, and to this day the country still struggles with the byproducts of this history. Many of Anlong Veng's residents were former Khmer Rouge soldiers and cadres, and without a doubt many either participated or assisted in violent acts.

The reverse can also be said, which is that in studying the people of Anlong Veng, it might be easy to slip into an empathetic mindset in which the horrors of the regime and move-ment fade in relation to the stories and personal struggles of its individual members. Thousands of cadres and their families—including high-ranking communist leaders— were arrested and murdered throughout the country. The regime arrested, tortured, and killed members who joined the movement from its earliest days, and there was often little recourse or escape if one was suspected of disloyalty. Without a doubt, terror became a universal blanket that enslaved the society as a whole.

Even after the regime fell, the Cambodian population—both within and outside of Khmer Rouge-controlled territory—suffered incredibly. The over-ten-year war between Vietnam¬ese forces and the Khmer Rouge produced thousands of casualties on all sides. For several years the people were largely dependent on humanitarian assistance, and famine and dis¬ease were a constant threat.

The purpose of this book is to neither condemn nor venerate the people of Anlong Veng. Instead, we hope to provide a view into an under-studied community and a voice to an otherwise under-heard people. It is a universal rule that conflict resolution and peace is built and sustained on an open-minded discussion of the past.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|