Short

Course on Islam, Gender, and Reproductive Rights,

Southeast Asia, 4-25 June 2005, Indonesia

Funded

by the Ford Foundation

Organized by the Center for Women’s Studies, State Islamic

University,

Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta, Indonesia

The Study

of the Qur-An vs. Modern Education

for Islamic

Women in Cambodia

Farina So

Documentation Center of Cambodia

Cambodia’s

Muslim community (the Cham) faces many problems, including poverty,

relative isolation (outside the capital of Phnom Penh, most Muslims

live in communities that lack access to such basic infrastructure as

good roads, water, electricity, telecommunications, and newspapers),

and negative cultural perceptions (some members of the majority

Buddhist community and minority ethnic groups still view the Cham

with suspicion, if not superstition).

In 2005,

the Cambodia Television Network aired a program, “Manpower and

Destiny,” that for the first time featured a Cham as a lead

character. However, the series depicted the Muslim as an indolent

who depended on destiny rather than his own efforts. In addition,

the actor portraying the Cham character wears an earring (which

Muslim men are not allowed to do) and clothing that is supposed to

be worn for praying and religious ceremonies only. He also drinks

beer. An outcry from the Cham community contributed to the series

being taken off the air.

Muslim

women have traditionally faced a number of social and cultural

obstacles to their development, including fewer opportunities for

advancement than either the general population or Muslim men. These

translate into Cham women enjoying less access to adequate health

care, having lower status in society in terms of both family and

community decision making, lacking a voice in the political arena,

and lower educational attainment. This paper focuses on the last

area – education, which affects all the other problems women

experience. It also offers some solutions to improve their

situation.

Islam and

Education

Every Muslim

man’s and every Muslim woman’s prayer should be:

“My Lord!

Enrich me with knowledge.” Surah TA HA, 20:114.

For Muslims,

the Qur-An is the final word of Allah as revealed through his last

messenger Muhammad. This holy book contains guidance from Allah, not

only on how to find salvation but also on how people should live their

lives in the right way.

The Qur-An

begins with an important word: “Read.” It states that “The best form

of worship is the pursuit of knowledge,” and also that “The ink of the

scholar’s pen is more sacred than the blood of the martyrs.” The Qur-An

tells us that without education, it is difficult for people to

understand its teachings, and that education is vital for all aspects

of our lives.

However,

while the Qur-An says that both men and women should pursue knowledge,

it also places restrictions on women’s interactions with the outside

world (such as placing them under the protection of their parents),

and proscribes different rights for men and women owing to their

psychological and biological differences. This has limited women’s

ability to obtain modern academic educations, which has in turn

impeded their ability to become knowledgeable about the wider world

and to make intellectual and economic contributions to their families

and communities.

Literacy

in the Muslim World

One out of

every five people in the world today is Muslim. Yet only about 38% of

Muslims are literate. For women, the picture is even worse: in many

rural areas of the Islamic world, only about 5 out of every 100 women

can read and write. According to the United Nations Development

Programme, Muslim women also have the lowest economic and political

participation of any group of women in the world.

Many scholars

have linked the lack of education to the lack of economic

opportunities and development that are now plaguing many Muslim

countries. So, low levels of literacy are at least partly responsible

for the poverty in which many Muslims live today. It is likely that

people who lack modern education will fall further and further behind

and become mired in their poverty.

The world is

changing fast, and

how we

live our lives and the ways in which we earn a living play a very

important part in our future. Without strong human resources and

capital, it will be difficult for Muslims to advance. To use these

human resources wisely and to keep up with the rest of the world,

Muslims need

education, including such broad studies as science, mathematics,

economics, and of course, advanced technology.

Without a

doubt, women represent half of the Muslim world’s human resources, and

can play an indispensable part in development. They should not be

confined to the kitchen. Rather, they should be encouraged to pursue

their studies, have careers that make a contribution to their society,

and be empowered in decision making processes.

A Profile

of Cambodia’s Muslims

About 90% of

Cambodia’s 13.6 million people are Khmers, who practice Buddhism. The

other 10% comprise a variety of ethnic and religious groups, including

Vietnamese, Chinese, highland minorities, and Chams.

The Chams are

a diverse group; most of them descend from the Kingdom of Champa and

Malays (primarily of Javanese extraction). The Kingdom of Champa

controlled what is now south and central Vietnam from the 2nd

through the 17th centuries; its peoples converted from

Hinduism to Islam in the 15th century.

The Champa

Kingdom’s defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese in the 15th

and 18th centuries forced the Champa king and many of his

followers to flee to Cambodia, where most Cham live today. The Malay

influence on Chams is felt through their language, which is based on

Arabic and is akin to Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Indonesia.

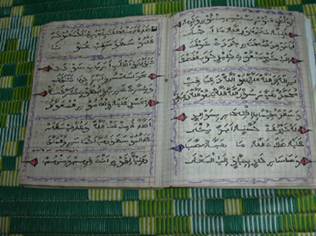

Cham script,

in a book for the celebration of Muhammad’s birthday

All of

Cambodia’s Cham Muslims are Sunnis of the Shafii School. They practice

two types of Islam:

§

There

is a small traditionalist branch (about 35 villages) which retains

many ancient Muslim and pre-Muslim rites and traditions (e.g., from

Buddhism and Hinduism), and takes a more liberal interpretation of

Islam. This community’s attitudes toward women are also more liberal;

for example, few women cover their heads outside the area of the

mosque.

Cake

procession to the mosque during

Women at the mosque in Sre Prey

the Malut

festival in the traditional village

of Sre Prey,

O'Russey sub-district,

Kampong

Tralach district,

Kampong

Chhnang province

§

The

far larger orthodox Cham community takes a more conservative approach

to the practice of Islam and has adopted many Malay customs and

practices. In these communities, women lead more separate lives than

men. Women in the orthodox community generally wear the veil on their

heads and in a few communities are completely covered except for their

eyes.

However, in

neither community do women appear to participate actively in social or

political affairs, instead, they follow the instructions of community

religious leaders or their husbands and fathers. The author has not

observed any differences between the two communities in terms of the

percentage of women who attend schools. This may be due more to

external factors (the banning of head scarves by many public schools)

than community willingness to educate girls, as discussed below.

Like other

Cambodians, most Chams live in rural areas, where they are primarily

engaged in fishing and farming. Most of them are concentrated along

rivers in 6 of Cambodia’s 22 provinces: Kampong Cham, Kampot, Pursat,

Battambang, Kandal, and Kampong Chhnang.

It is believed that in 1975, when the Khmer Rouge took control of

Cambodia, the country’s Cham population was around 700,000. The Chams

suffered a devastating loss of people under the Khmer Rouge regime

(called Democratic Kampuchea), with an estimated 400,000 to 500,000

dying. Today, about 500,000 Chams live in Cambodia. There is evidence

to suggest that the Khmer Rouge persecuted the Cham Muslims on

religious and ethnic grounds. Documentation Center of Cambodia scholar

Osman Ysa has posited that Chams

were killed a rate

nearly double to triple that of the general Cambodian population

during the Democratic Kampuchea regime (Oukoubah: Justice for the

Cham Muslims under Democratic Kampuchea, DC-Cam, 2002).

During the

period of Khmer Rouge rule (April 1975 – January 1979), Chams were not

allowed to worship. Most of the country’s 130 mosques were destroyed

or desecrated, and only about 20 of the most prominent Cham clergy in

Cambodia survived the regime.

Like people

throughout Cambodia at the end of Democratic Kampuchea, about

three-quarters of the regime’s survivors were women. These widows

became the heads of their families and bore most of the responsibility

for putting their country back together (it was a policy of the regime

to kill educated people; thus, most of the survivors of Democratic

Kampuchea could not read or write). Many also suffered from

psychological problems and trauma as a result of the loss of family

members, hunger, forced labor, imprisonment, and other privations

during the regime.

Despite

women’s crucial role in helping Cambodia to recover, traditional

gender inequality subsequently resurfaced in all realms of Cham life,

including that of education. This has left a large proportion of

Cambodian Muslim women with few literacy skills today.

Education for

Cambodia’s Muslims

The Larger

Cham Community

Most of

Cambodia’s Muslims do not seem to be aware of the importance of modern

education and its role in economic development. Instead, imams,

hakim and tuan (community religious leaders), who have a

powerful influence on their communities, stress religious education

almost exclusively. To make matters worse, scholars seem to have

neglected the role of general education and its importance for

the

Cambodian Muslim community.

When other Islamic countries have studied education here, they, too,

are largely concerned with religious education.

Girls

studying Islamic texts in a traditional Cham village,

O'Russey

sub-district, Kampong Tralach district

In Cambodia,

the percentage of uneducated Muslim people is high, and even most

hakim and tuan are illiterate. They don’t have general

knowledge and cannot write in Khmer, which is Cambodia’s

official

language.

Because these

leaders lack modern education, they address disputes in the

traditional way. For example, when a conflict arises between

villagers, the imam, hakim and tuan usually

resolve it based on their personal experience. But their solutions

don’t always employ logic or strategy, and as a result the conflicting

parties often do not reconcile effectively. Finding solutions that

work requires a wide range of knowledge and experience that include

both religious and modern ways.

Further, few

of the tuan in rural areas who teach Muslim children about the

holy Qur-An and Islamic law have an adequate standard of living

because they do not have a modern education. If they had more than

religious knowledge, they could use their skills to help improve their

community’s standard of living, as well as enhance their own lives.

Last year, I

began working on a project that is recording the oral histories of the

Chams during the Khmer Rouge regime. As part of my work, I asked

religious leaders and lay people to complete questionnaires on their

experiences and views relating to this period of history. I have

observed that most villagers, hakim and tuan cannot

write well or don’t know how to write. When I asked them why, most

complained that they are illiterate and some said that they lack

education.

Many young

Cambodian Muslims recognize that a modern education is vital to their

future, but have little to no opportunity to get one beyond high

school. So instead, they study Islam and acquire mostly religious

knowledge. In answering my questions about studying abroad, they said

they had no alternative but to pursue the study of religious subjects.

The

Educational Status and Prospects for Cham Women

Democratic Kampuchea

left in its wake a legacy of illiteracy, and women (both Cham and

Buddhist) suffer from higher rates of illiteracy than men to this day.[1]

Much of this phenomenon can be attributed to economic and cultural

factors.

Poverty is a

pervasive and self-perpetuating influence on women’s lack of

education. Many Cham girls, like their Buddhist counterparts, are

unable to complete primary school because they are put in charge of

taking care of their younger brothers and sisters at home, doing

household chores such as gathering firewood and water, and working on

the family farm, especially at harvest time. In addition, such direct

expenses for school as fees, clothing and notebooks, as well as the

indirect costs of the loss of labor to the household, can be

prohibitive for many families. This represents a vicious cycle,

wherein poverty forces girls to labor for the family instead of

attending school. Without an education, women have little means of

earning a living outside the home, reinforcing their impoverishment in

the future.

Women in

conservative Kampong Keh village are studying in a religious class.

They have

been forced to drop out of school because of the policy banning head

scarves in

classes. (Kampong Keh sub-district, Trapeang Sangke district,

Kampot

province)

Cultural

factors also have a strong role in preventing many Cham women from

completing school. Cham girls begin their religious studies at around

the age of six; these classes are taught by a tuan in a girl’s

village or one nearby. They are required to wear a headscarf, long

blouse and skirt, and to strictly follow codes of Islamic behavior.

However, once they enter puberty and prepare to enter secondary

school, problems begin. Formal education is not mandatory in Cambodia

and in most secondary schools, the wearing of head scarves is not

permitted. This policy places both girls and their parents in a

dilemma.

If the

parents insist that the daughter wear a scarf in class, she will be

asked to leave school. But if they decide to let the girl remove her

scarf, she will be in direct violation of Islamic religious principles

and tradition. Thus, many parents elect to have their daughters drop

out of school; afterward, the girls often help at home with housework

and study religion. The daughters themselves have little say in the

matter.

These three

women from conservative O-kcheay village dropped out of school

at the age of

10 or 11 (Wat Tamim subdistrict, Sangke district, Battambang province)

The author

made several trips to Kampot and Battambang provinces during 2004 and

2005 to learn about some of the problems Cham women face in their

communities. In the village of Kampong Keh in Kampot province, for

example, interviews were conducted with imam, hakim,

tuan, and a group of approximately 35 Muslim men and women around

the age of 16.

In this

orthodox Cham village, where about 250 families live, it is difficult

to see Muslim women in secondary school; instead, most dropped out at

when their primary education was completed. When asked why this was, I

was told that the reason was due to Islamic teaching, norms, and

economic necessity. The requirements for girls to cover their heads in

both class and public, and Muslim codes of behavior meant that girls

could not continue with their schooling.

There was

little difference in the orthodox village of O-kcheay in Battambang

province, where the practice of Islam is very strict. Women there wear

a black veil that covers all of their faces except the eyes and long

black dresses. There, I interviewed two women who had given birth on

the day the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh and began forcing its

inhabitants to leave the city: April 17, 1975.

The daughter

of one of the women, who is now age 30, was nearly completely covered

according to the prescriptions of Islamic code. She told me that she

dropped out of school at a very young age because of her school’s

prohibition on head coverings. In addition, poverty forced her to

stay at home. This woman stated that she very much wanted an academic

education, but that circumstances had forced her to give up hope of

obtaining one.

The picture

for urban Muslim women is somewhat brighter: they are generally better

educated than their rural sisters and many of them work outside the

home, largely as a result of economic necessity. But in urban areas,

too, “economic necessity” can also mean that a girl must drop out of

school and work to support her family. In addition, many parents feel

that girls do not need to pursue more than a primary school education;

all they need to do is to be able to read and write. And many men feel

that their wives’ and daughters’ place is at home, taking care of the

children.

In both rural

and urban poor families, which must often make economic tradeoffs in

order to survive economically, the decision is often made to allow the

male children to attend school while the daughters stay at home. In

addition, men are encouraged and given preference in applying for

scholarships to complete their higher educations. This has helped keep

literacy rates at low levels for Cham women. Last, the position of

women – no matter what their religious background – has not been a

matter of concern to the Royal Government of Cambodia.

The Cambodian

Muslim Students Association conducted a survey on the position of men

and women in Cambodia in 2003. Their data show that men play a much

more important role than women in the community. For instance, only

one woman appears in the list of the country’s seventeen Muslim

leaders in the country (Table 1). It is worth noting that today, no

Chams have positions of authority in the Ministry of Education

(earlier, however, H.E. Tollah was minister of education and he was a

Cham).

Conclusions

The impact of

failing to understand modern education, social needs, the advances of

technology, and in particular, the role of women in development, will

be to weaken the community deeply in terms of rising violence,

illiteracy and poverty. How can Chams find jobs if they have only

religious training? How can they develop their community if they have

little knowledge of the modern world? And why has the Cambodian Muslim

community lagged so far behind its neighbors in Southeast Asia in

terms of education, health, and economic infrastructure?

Addressing these problems will depend on Muslim themselves, and on

advocacy and technical assistance from the national and international

communities. The

recognition

and acceptance of Muslim women’s roles in development and empowering

them in the education, economics, social, health and political spheres

is the best solution for the Cambodian Muslim community.

To develop the country and raise literacy, Cambodia must keep

up with global changes by obtaining

modern education in addition to religious knowledge. Hakim,

imam and tuan should, for example, be

educated in

management and administration in order to resolve community problems.

All Chams should also be encouraged to pursue higher education. And

last, Allah said that human beings should have both modern and

religious knowledge (Ilmu Dunia and Ilmu Akhirat) in order to live in

prosperity. This includes women, who will not be able to advance in

society without proper knowledge and education.

On behalf of Muslim women, I would like to appeal to both Muslim and

non-Muslim countries to grant more scholarships to women so they can

obtain general educations. And schools should reconsider their stance

on the wearing of head scarves in public schools, which has prevented

many Cham women from obtaining an education. These simple actions will

give Cambodia’s Muslim women opportunities to play a crucial role in

their communities, and help them prosper in the economic, political,

social, health, and other arenas.

Table 1

Cambodia’s Muslim

Leaders

for the 3RD

Mandate (2003-2008)*

|

No. |

Name |

Position |

Party** |

|

1 |

H.E.

Othsman Hassan |

§

Secretary of State, Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training

§

Advisor and Special Envoy to Prime Minister Samdech Hun Sen

§

President of

Cambodian Muslim Development Foundation

(CMDF)

§

Secretary General, the Foundation for Cambodian People’s Poverty

Alleviation (PAL)

§

Vice-Director of Cambodian Islamic Center (CIC)

§

Patron of Islamic Medical Association of Cambodia (IMAC)

§

Chairperson of the Islamic World and Malay to Cambodia (IWMC) |

CPP |

|

2 |

H.E.

Zakarya Adam |

§

Secretary of State, Ministry of Cults and Religion

§

Vice President of CMDF

§

General Secretary of CIC

§

Vice-Chairperson of IWMC |

CPP |

|

3 |

H.E.

Sith Ibrahim |

§

Secretary of State, Ministry of Cults and Religion |

FUN |

|

4 |

H.E.

Dr. Sos Mousine |

§

Under Secretary of State, Ministry of Rural Development

§

President of Cambodian Muslim Students Association and IMAC

§

Member of CMDF

§

Under-General Secretary of CIC |

CPP |

|

5 |

H.E.

Sem Sokha

|

§

Under Secretary of State, Ministry of Social Affairs and

Veterans

§

Member of CMDF |

CPP |

|

6 |

Her.E. Madame Kob Mariah |

§

Under Secretary, Ministry of Women

§

General Secretary of Cambodian Islamic Women Development

§

Cambodian Islamic Women’s Development Organization Association

and member of CMDF |

CPP |

|

7 |

H.E.

Msas Loh |

§

Under Secretary of State, Office of the Council of Ministers

§

Patron of Cambodian Islamic Association |

CPP |

|

8 |

H.E.

Paing Punyamin |

§

Member of Parliament representing Kampong Chhnang

§

Member of CMDF

§

Executive Member of CIC |

CPP |

|

9 |

H.E.

Sman Teath |

§

Member of Parliament representing Pursat

§

Member of CMDF

§

Under-General Secretary of CIC |

CPP |

|

10 |

H.E.

Ahmad Yahya |

§

Member of Parliament representing Kampong Cham

§

President of Cambodian Islamic Development Association (CIDA) |

SRP |

|

11 |

H.E.

Wan Math |

§

Member of the Senate

§

President of Cambodian Islamic Association |

CPP |

|

12 |

H.E.

Sabo Bacha |

§

Member of the Senate |

FUN |

13

|

Mr. Sem Soprey

|

§

Vice Governor

of Kampong Cham province

§

Member of CMDF |

CPP

|

14

|

Mr. Saleh Sen

|

§

Vice Governor

of Kampong Chhnang province

§

Member of CMDF

|

CPP

|

|

15 |

H.E.

Ismail Osman |

§

Advisor to Samdech Krompreah Norodom Rannarith, President of the

National Assembly |

FUN |

|

16 |

General

Chao

Tol |

§

Assistant to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of

Cambodia |

CPP |

|

17 |

General

Sen

Komary |

§

Head of Department of Health, Ministry of National Defense

§

Member of IMAC |

CPP |

*

Three other leaders of the Muslim community – H.E. Tollah, H.E. Math

Ly, and Sou Zakarya, have died since 2003. All three were men.

**

CPP : Cambodian People’s Party

FUN : FUNCINPEC Party

SRP : Sam Rainsy Party (opposition)

|