|

|

Buddhist Cremation Traditions for the Dead

and the Need to Preserve Forensic Evidence in Cambodia

Wynne Cougill

[1]

Documentation Center

of Cambodia

When

Vietnamese-led forces invaded Cambodia in late December 1978 and

toppled the Khmer Rouge, they discovered ample evidence of the mass

death brought about by Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea regime. The

death toll during the nearly four years that the Khmer Rouge held

power was relatively small compared to those of many modern genocides

(an estimated 1.7 million people perished from execution or as the

result of starvation, disease, or forced labor), but no other genocide

has approached Cambodia’s as a percentage of the population. The Khmer

Rouge were responsible for the loss of about a quarter of the

country’s people.

In the

wake of the devastation the Khmer Rouge visited on Cambodia, there was

little public outcry over the disposition of the bones found in the

mass graves that dotted the country, most of which were left untouched

and exposed to the elements. Nearly all Cambodia’s infrastructure had

been destroyed during the regime (schools, banks, post offices, and

telecommunications were shut down, and religious structures were

converted into prisons) and most of its educated people had died,

leaving survivors more concerned with the struggle to live than

attending to the dead.

After

seven years of negotiations, in October 2004, the Royal Cambodian

Government and the United Nations ratified an agreement on the

prosecution of crimes committed during Democratic Kampuchea and

amendments to the law that establishes Extraordinary Chambers for a

tribunal of the regime’s senior leaders. In addition to their

historical importance, the bones in Cambodia’s mass graves will

provide physical evidence of mass murders at the trials. But more

recently, a debate has surfaced over their treatment and preservation.

Early Efforts to

Preserve the Bones

The

Vietnamese-installed government of Cambodia (the People’s Republic of

Kampuchea, PRK) sought to preserve the skeletal remains in Cambodia,

at first to prove that their ideological and political enemy China had

been behind the mass murders in Cambodia. Later, they viewed the bones

as evidence of genocide and thus a justification for the PRK’s control

of the country. (At this time, the United Nations and several Western

governments still recognized the Khmer Rouge as the country’s

legitimate government.) Two important sites in the Phnom Penh area

were the focus of their attention, and have become symbolic of the

horrors of Democratic Kampuchea today.

The

first is Tuol Sleng, a former Phnom Penh high school that served as a

secret, state-level prison during Democratic Kampuchea (it was known

to the Khmer Rouge by its code name S-21). According to documents

found in and around the prison, at least 14,000 enemies of the state

were detained here, and when the Vietnamese entered Phnom Penh on

January 7, 1979, they found less than a dozen survivors.

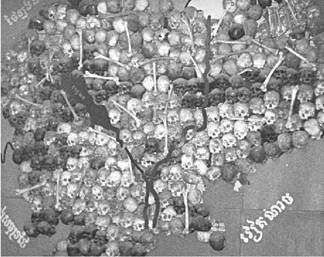

At

Tuol Sleng (which was made into a national museum in 1980 using the

massive documentation that survived at the site), the PRK created a 12

meter-square map containing 300 exhumed skulls, with Cambodia’s man y

rivers painted in blood red. The remained on public display until

2002, when it was dismantled. Today, the skulls from the map are

housed in a wooden case enclosed by glass.

The skull map at

Tuol

Sleng

Genocide

Museum

s

The

second is the “killing field” of Choeung Ek, which was discovered

about a year after the invasion. Most of Tuol Sleng’s inmates, in

addition to many other Cambodians – at least 20,000 people – were

executed at this site, which is about 15 km from the prison. Victims

were usually forced to kneel at the edge of the mass graves while

guards clubbed them on the back of the neck or head with a hoe or

spade.

Large-scale excavations took place at Choeung Ek in 1980: about 89

mass graves were disinterred out of the approximately 130 in the

vicinity. Nearly 9,000 individual skeletons were removed from the

site with the assistance of Vietnamese forensic specialists. The

remains were treated with chemical preservatives and placed in a

wooden memorial pavilion with open walls. To the dismay of many, PRK

officials also “arranged” bones in a decorative manner for

photographs.

Skull arrangement

at Chhoeung Ek

s

In

the decade

immediately following the

toppling of the Khmer Rouge, many national and local-level memorials

were constructed throughout Cambodia. A new memorial was built at

Choeung Ek in June 1988. Its 62 meter tall

concrete stupa contains a sealed glass display housing about

8,000 skulls. Vietnamese General Mai Lam, the archivist of Tuol Sleng

Museum and designer of the skull map, characterized the preservation

of human remains as “very important for the Cambodian people – it’s

the proof.”[2]

Choeung Ek Genocide Memorial Stupa

Buddhism and the

Preservation of Remains

About

95% of Cambodians practice Hinhayana Buddhism, which does not

prescribe cremation. But cremating the dead has been a tradition in

Cambodia and other Buddhist societies in Asia for centuries. Many

Cambodians believe that cremation and other rituals for the dead help

ease the deceased’s transition to rebirth. After cremation, Cambodians

store their family members’ ashes in a stupa so their souls can

be liberated for reincarnation.

Overlaying this tradition is the syncretistic practice of Buddhism in

Cambodia, which combines elements of Hinduism and animism. Among the

many spirits present in the animistic world are those of the dead. The

spirits of people who died unnatural deaths are considered to be the

most malevolent of these; because their spirits cannot rest, they

haunt the living and cause them misfortune.

In

the case of especially inauspicious deaths, such as by violence or

accident, it is widely believed that the dead person’s spirit or ghost

remains in the place where he or she died, and does not move on to

rebirth. One researcher has noted that “many

Cambodians consider Choeng Ek a highly dangerous place and refuse to

visit the Memorial. In addition, to have uncremated remains on

display is considered by some to be a great offence, and

tantamount to a second violence being done to the victims.”[3]

The Controversy

over the Remains

Most

Cambodians – the general population, the religious community, and the

government – seem to support the preservation of skulls and other

human remains of Democratic Kampuchea. (This support is reinforced by

an underlying belief in Buddhist tradition that people can cremate

only the remains of their family members. Because virtually no

individuals in the country’s killing fields have been identified from

their remains, cremation could pose some obstacles in Cambodia.)

The

Cambodian Government has long supported the preservation of the bones

as evidence. Prime Minister Hun Sen, for example, issued instructions

for the remains in late 2001:

In order to preserve the remains as

evidence of these historic crimes and as the basis for remembrance and

education by the Cambodian people as a whole, especially future

generations, of the painful and terrible history brought about by the

Democratic Kampuchea regime…the government issues the following

directives:

1.

All local authorities at the

province and municipal level shall cooperate with relevant expert

institutions in their areas to examine, restore and maintain all

existing memorials, and to examine and research other remaining grave

sites, so that all such places may be transformed into memorials.[4]

Neither

has there been an outcry from the Buddhist clergy. In fact, many monks

seem to welcome the preservation of remains in situ. A local

patriarch monk, who had initiated the construction of a memorial for

the remains from Sa-ang prison in Cambodia’s Kandal province in late

1999, told staff from the Documentation Center of Cambodia:

One reason I got the idea to construct

this memorial is that one member of my family was killed at Sang

Prison. Another reason is that I observed the remains in a sad state,

just sitting there exposed to the sun, wind, and rain. The remains

have decayed and have even been eaten by cows. That inspired me to

think that if the remains continued to lie in the state they were in

they would certainly vanish and no evidence would be left for younger

generations to see. In addition, if Buddhist followers wanted to come

to light incense and pay homage to commemorate the souls of the dead,

there was not a place for them to do so. So this idea of building a

memorial for the remains came to my mind.

But the loss of the remains is what I have

worried about the most. Because if people say “many died there,” but

there are no remains there, how can we believe? So preserving the

remains is the most important reason. I am not conceited. Many people

have contributed their money. I did not build this on my own. I do not

want to lose the evidence, so that people from various places can come

to pray and pay homage to the dead. And I will request the district

governor that this memorial for the remains should exist forever. And

I am thinking of having monks stay there and for people to come and

pay homage because some souls of the dead have made their parents or

children dream of them, and told them that they are wandering around

and have not reincarnated in another world. I want to have monks

meditating there so that the souls of the dead will rest in peace. In

Buddhism, when someone dies and their mind is still with this world,

then their souls wander around. The remains are a legacy for the

younger generation so that they may know how vicious the Khmer Rouge

regime was, because the young did not experience the regime. I

experienced this regime. Some lived through this regime as children

but they still do not believe; how can those who did not live through

believe? What can they base belief on?

[Speaking of the

possibility that authorities would require that the bones be moved] I

would not dare to oppose them at all. I could only request that they

do not burn them, but give them to me. Please do not touch the remains

because I have a stupa for them already. If they do not want that, I

can bring them to my pagoda here. But if they still insist that the

remains be burnt, I dare not oppose them. In my opinion, if they do

not want us to keep the remains there, I would like to keep them in my

pagoda so that people can come and hold religious ceremonies for their

dead relatives.[5]

Instead, opposition has come mainly from former King Norodom Sihanouk

and some members of Cambodia’s royalist party, FUNCINPEC. On February

23, 2001, Sihanouk wrote to Hun Sen asking that the skulls be removed

from the map at Tuol Sleng and “cremated in the Buddhist way” so their

souls could find rest.[6]

Hun Sen later indicated his willingness to hold a national referendum

on the issue after any trials of former Khmer Rouge.

Sihanouk also posted a letter on his website in February 2004,

decrying the way the bones of Khmer Rouge victims have been left out

and exposed around the country. He wrote that those killed by the

Khmer Rouge will “never have peace and serenity” and that their

remains should be cremated in nationwide religious ceremonies.[7]

On

April 17, 2004, Sihanouk marked the 29th anniversary of

Phnom Penh’s fall to the Khmer Rouge by calling for the cremation of

victims of the killing fields. “We are Buddhists whose belief and

customs since ancient times have always been to cremate the corpses

and then bring the remains to be placed in the stupa at the

pagoda,” he wrote.[8]

An Effort to

Resolve the Controversy

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) has made a number of

efforts to reconcile the views of the king and respect for Buddhist

beliefs with the needs for public education and forensic evidence from

the genocide. For example, in 2002, it replaced the skull map with a

satellite map of Cambodia identifying the locations of prisons and

mass graves from Democratic Kampuchea. The King subsequently wrote to

DC-Cam, “I would like to express my profound gratitude and warm

appreciation of your unique state-of-the-art initiative in zooming the

map of Cambodia with genocide sites to replace the existing skull map

being displayed at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.”[9]

In

2003, the Center provided a large number of skulls from Choeung Ek and

other parts of Cambodia to a team of North American forensics

specialists.[10]

The experts chose ten skulls for analysis. In February 2004, DC-Cam

mounted an exhibition of the skulls at Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

Entitled “The Bones Cannot Find Peace until the Truth they Hold in

Themselves has been Revealed,” the exhibit sought to demonstrate the

value of forensics in documenting the Khmer Rouge’s crimes against

humanity and to educate the public about the types of information that

can be scientifically gathered from victims’ remains.

Originally, DC-Cam wished to display the skulls for public viewing.

However, out of respect for King Sihanouk and other Cambodians who are

uncomfortable with the idea of boxing human remains, the Center looked

for another solution. It thus housed the skulls in a separate room at

Tuol Sleng, which is open only to officials

(e.g.,

prosecutors at the Khmer Rouge tribunal). Their final disposition will

be determined once the tribunal is over.

The

skulls rest on identical pedestals built from slightly overlapping

wooden slats. Spaces have been left between slats so that air can

reach the skulls, thus allowing the spirits to come and go as they

wish. To protect the skulls, the Center placed them in clear,

five-sided Plexiglas cases secured with soft silicone caulk. The cases

can be removed by cutting the caulk with a razor blade, allowing the

skulls to be cleaned or moved. For the exhibition itself, the Center

chose to photograph the skulls, which were accompanied by text

explaining the type of trauma to each skull.

Photograph from the DC-Cam

Tuol Sleng Forensics Exhibition

1) Cranium of

a man, 25 to 45 years old.

Gunshot wound

of entrance in the left frontal convexity with the bullet passing into

the brain from right to left and downward on a 45-degree angle (as

indicated by the “keyhole” effect). [Catalogue No. TSL13, 2A50700]

King Sihanouk has proposed building a stupa at the old royal

capital of Udong to house the ashes from the cremated skeletons. Once

the Khmer Rouge tribunal is over, it may finally be possible to lay

the victims to rest more than a quarter of a century after the

genocide.

[1]

Wynne Cougill began working as a volunteer editor and writer for

the Documentation Center of Cambodia in early 2000. She is the

lead author of Stilled Lives: Photographs from the Cambodian

Genocide (DC-Cam, Phnom Penh, 2004), and has been resident

with the Center in Phnom Penh since January 2004.

[2]

Hughes, R. (2004). Memory and sovereignty in post-1979 Cambodia:

Choeung Ek and local genocide memorials, in S. Cook (ed.) New

perspectives on genocide:

Cambodia and Rwanda.

Yale Center for International and Area Studies: New Haven, p. 271.

[3]

Ibid., p. 76. A few caveats are in order regarding these

observations. First, Cambodian Buddhists do not bury their dead,

and thus do not visit grave sites as such (those of Chinese

descent do bury their dead and honor them by grave visits,

however). Thus, most Cambodians view Choeung Ek as a stupa,

not as a memorial. Second, the offense taken is a natural human

reaction: the bones may be those of one’s relatives, which makes

many people reluctant to visit the memorial. Last, some Cambodians

do view Choeung Ek as a dangerous place because of the ghosts

present, not because they fear physical violence by robbers, etc.

Those who have visited this site do so to share their sorrow;

thus, Choeung Ek can be viewed as a place of healing for

survivors.

[4]

Royal Government of Cambodia (2001).

Circular on

preservation of remains of the genocide (1975-1978), and

preparation of Anlong Veng to become a region for historical

tourism. Phnom Penh, 14 December, copy held at the Documentation

Center of Cambodia, 1 page.

[5]

Phat, Kosal. (2004). “Necessity of Preserving Physical Evidence.”

www.dccam.org/Archives/Physical/Importance.htm - 50k

[6]

Original letter in the possession of the Documentation Center of

Cambodia.

[7]

http://openhere.com/current/414456498.stm

[8]

The Cambodia Daily.

April 19, 2004.

[9]

Bail, Molly and Lor Chandara, Skull map at museum may be removed,

The Cambodia Daily, October 17, 2001.

[10]

DC-Cam uses global satellite position mapping combined with

fieldwork to document mass graves nationwide. To date, it has

identified over 380 genocide sites containing more than 19,000

mass graves (these are defined as any pit containing 4 or more

bodies, although some graves hold over 1,000) dating from the

Khmer Rouge regime. In addition, the Center has documented 189

prisons from Democratic Kampuchea and 80 genocide memorials.

|

|